The globe was already in a grave mental health crisis when the COVID-19 epidemic began. Despite the fact that at least a quarter of the population was doomed to suffer from mental illness at some point in their life, the health authorities took no steps to address the problem. And the predicament created by the new coronavirus only worsened.

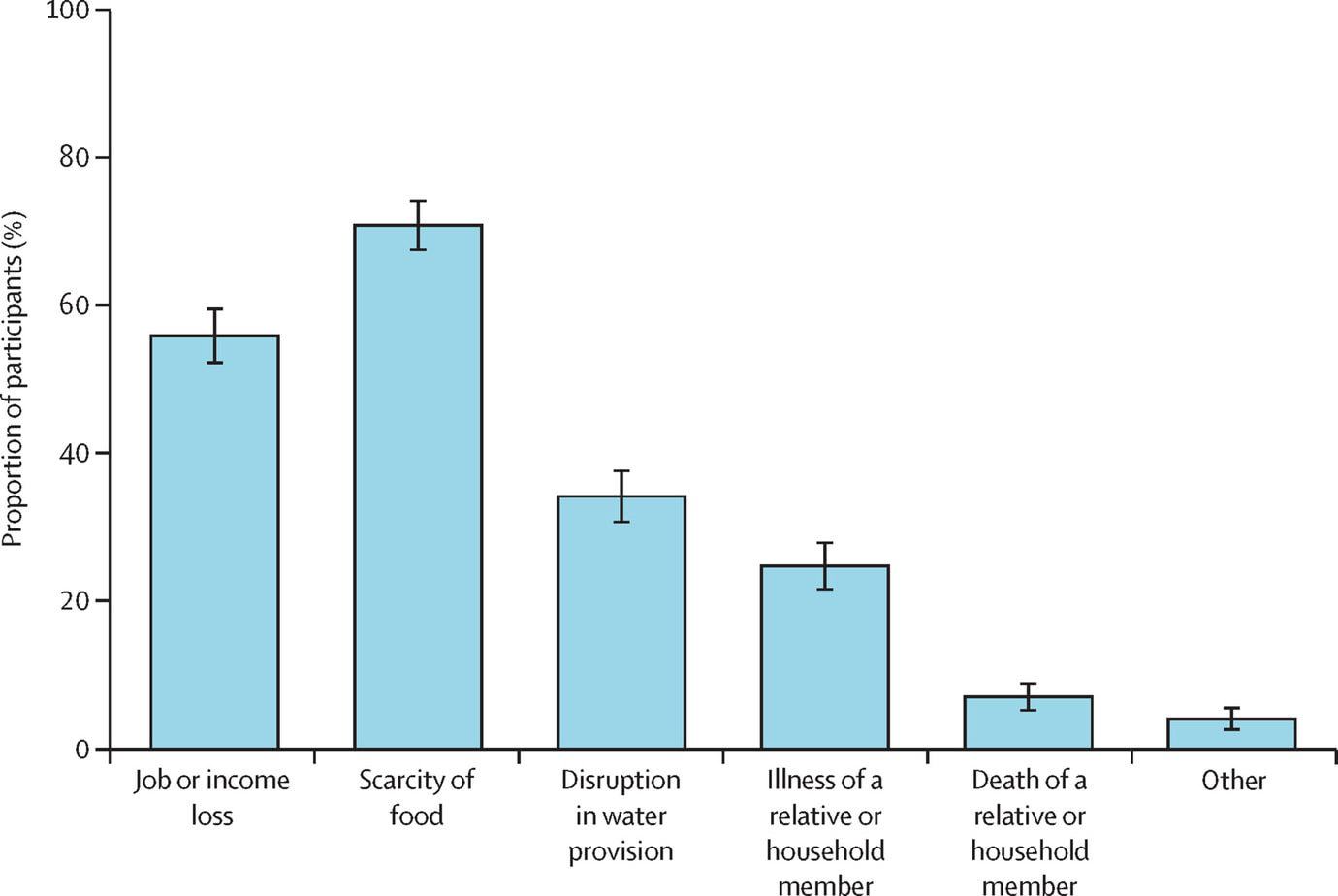

Two of the key catalysts were the population’s physical isolation, as well as the dread and perplexity caused by the virus’s rapid impact on health. However, economic hardships, disinformation, and (often upsetting) rumours about everything surrounding covid-19 all played a role.

Not to mention that being exposed to inconsistent, untrustworthy, or information that focuses solely on the negative sides of a scenario can lead to mental health issues including sadness and anxiety.

Children and teenagers have been the ones who have felt the brunt of the pandemic’s psychological toll. They have experienced longer and more severe negative repercussions without the controlled environment of school, and after losing family routines and the ability to participate in sports or simply go out with friends. Eating disorders and suicide attempts were the stars on the outskirts of adolescence and youth.

Front-line health professionals, who have suffered from compassion fatigue among other things, have also struggled.

We’ve also breached that type of implicit agreement this year, not to mention depression, the world’s most common mental disorder. Furthermore, it appears that we are now realising that seeking professional assistance when we need it does not make us weaker, but rather a strength.

It is a type of secondary stress that happens in the therapeutic support connection when the healthcare professional’s emotional capacity overflows in order to cope with the empathetic commitment to the patient’s suffering.